Defamation is a critical issue in law, intersecting the realms of free speech, reputation, and societal values. It’s a topic that has evolved over centuries, shaped by landmark legal cases, and influenced by cultural norms. Understanding defamation involves navigating complex legal principles, constitutional considerations, and societal implications. This comprehensive blog aims to provide an in-depth exploration of defamation from a legal perspective, focusing on the key elements of a defamation claim, defenses, and the influence of the U.S. Constitution on defamation law. We will also discuss the broader implications of defamation in society and how it affects individuals, public figures, and the media.

1. Introduction to Defamation

Defamation, as a legal concept, strikes at the heart of two fundamental values in society: the right to freedom of speech and the right to protect one’s reputation. The tension between these values has led to the development of a complex body of law that seeks to balance these interests. Defamation law provides a remedy for individuals whose reputations have been unjustly tarnished by false statements, while also recognizing the importance of free speech, especially in the context of public debate and the media.

In the digital age, where information spreads rapidly and widely, defamation has taken on new significance. The rise of social media platforms and online news sources has made it easier for defamatory statements to reach a large audience, potentially causing significant harm to individuals and businesses. This has led to a growing number of defamation cases, with courts having to navigate new challenges posed by the online environment.

2. The Legal Definition of Defamation

Defamation is a tort, a civil wrong that can result in legal liability. It involves the communication of a false statement that harms the reputation of an individual, business, or organization. The law of defamation is designed to protect people from unwarranted attacks on their character while also ensuring that freedom of expression is not unduly restricted.

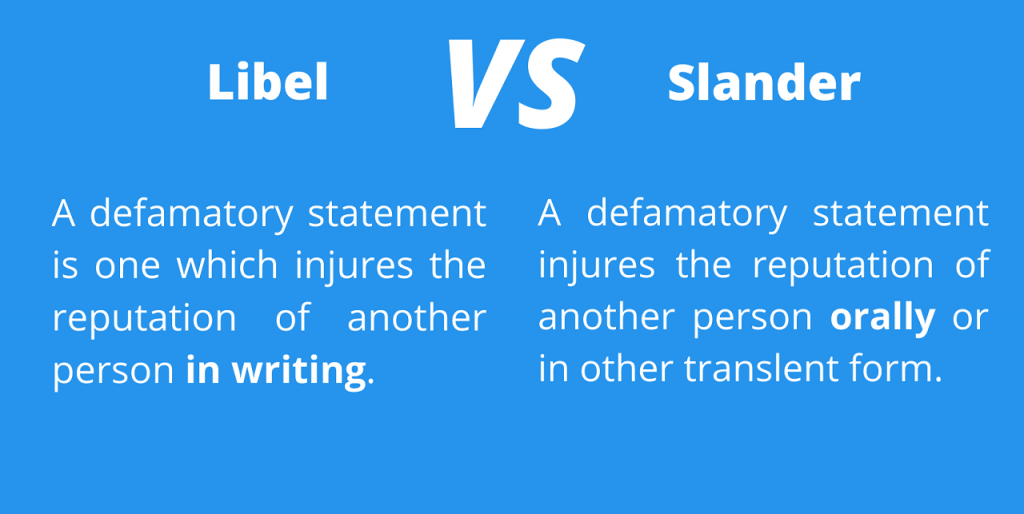

Defamation can take two forms: libel and slander.

- Libel refers to defamatory statements that are made in a permanent form, such as written words, images, or other published material.

- Slander, on the other hand, refers to defamatory statements that are made in a transient form, such as spoken words or gestures.

The distinction between libel and slander is significant because the legal standards and potential damages can differ between the two. Libel is generally considered more harmful because it has a lasting presence and can reach a wider audience, whereas slander is often seen as less severe due to its temporary nature.

3. Key Elements of a Defamation Claim

To succeed in a defamation lawsuit, the plaintiff must prove several elements. These elements form the foundation of a defamation claim and must be established for the plaintiff to recover damages.

False Statement

The cornerstone of any defamation claim is the existence of a false statement. The statement in question must be capable of being proven true or false. This means that opinions, no matter how offensive or hurtful, do not qualify as defamatory. For example, saying “I think John is a terrible manager” is an opinion and cannot be proven true or false. However, a statement like “John embezzled funds from the company” is a factual assertion that can be verified, making it potentially defamatory if proven false.

In defamation cases, the burden of proof lies with the plaintiff, meaning they must demonstrate that the statement in question is false. If the defendant can prove that the statement is true, the defamation claim will fail.

Published to a Third Party

For a statement to be defamatory, it must be communicated to someone other than the plaintiff. This element, known as “publication,” is crucial because defamation law is concerned with the damage that occurs when a false statement is disseminated to others.

Publication can occur in various ways, including:

- Verbal communication: Speaking the defamatory statement to another person.

- Written communication: Publishing the statement in a book, article, social media post, or other written form.

- Broadcast communication: Airing the statement on television, radio, or online video platforms.

It’s important to note that even a single person hearing or reading the statement can satisfy the publication element. Additionally, the “repeater rule” holds that anyone who repeats a defamatory statement can also be held liable, even if they were not the original source of the statement.

By the Actor (Defendant)

The third element of a defamation claim is that the defamatory statement must have been made by the defendant. This means that the defendant must be the person who originated or repeated the false statement.

There are instances where the defendant might not be the original source of the defamatory statement but can still be held liable. Under the repeater rule, anyone who republishes or repeats a defamatory statement can be held responsible for defamation. For example, if someone overhears a defamatory statement and then shares it with others, they too could be sued for defamation.

Of and Concerning the Plaintiff

The defamatory statement must specifically refer to the plaintiff or be about a identifiable person. This is often referred to as the “of and concerning” element.

In most defamation cases, this element is straightforward, as the statement directly names or identifies the plaintiff. However, in some cases, the statement may not explicitly mention the plaintiff but still be considered defamatory if it is clear that the statement was about them. For example, if someone makes a statement about a “former African-American President,” it is clear who is being referred to, even if the name isn’t mentioned.

Additionally, the plaintiff must be identifiable as an individual. General statements that do not target a specific person, such as “all lawyers are dishonest,” cannot form the basis of a defamation claim because they do not identify a particular individual.

Tending to Cause Damage to the Plaintiff’s Reputation

The final element of a defamation claim is that the statement must tend to cause damage to the plaintiff’s reputation. The law requires that the statement be defamatory, meaning it must hold the plaintiff up to scorn, ridicule, or contempt in the eyes of a right-thinking segment of society.

This element is often the most challenging to prove, as it involves showing that the statement harmed the plaintiff’s reputation in a meaningful way. The harm can be economic, such as losing clients or business opportunities, or non-economic, such as damage to personal relationships or emotional distress.

Courts will typically consider the context in which the statement was made and the audience that received it. For example, a false statement that a professional archaeologist cannot read ancient Greek could be damaging to their reputation within the academic community, even if it might not seem defamatory to the general public.

4. Defenses Against Defamation

Defamation cases are not one-sided, and defendants have several defenses they can raise to counter a defamation claim. These defenses are designed to protect free speech and ensure that individuals are not unjustly penalized for statements that are true, privileged, or otherwise protected.

Truth as a Defense

The most powerful defense against a defamation claim is truth. If the defendant can prove that the statement in question is true, then the defamation claim fails. This is because the law of defamation is concerned with protecting individuals from false statements, not true ones.

For example, if a newspaper publishes a report that a public official was convicted of a crime, and the report is true, the official cannot successfully sue for defamation, even if the report damages their reputation.

Privilege: Absolute and Qualified

Privilege is another important defense in defamation cases. Privilege refers to certain situations where individuals are protected from defamation claims, even if their statements are false. Privileges can be either absolute or qualified.

- Absolute Privilege: Absolute privilege provides complete immunity from defamation claims, regardless of intent or truth. This privilege typically applies in specific contexts, such as statements made during legislative proceedings, judicial proceedings, or official government communications. For example, a witness testifying in court is protected by absolute privilege and cannot be sued for defamation based on their testimony.

- Qualified Privilege: Qualified privilege offers protection in certain situations, but it is not absolute. To be protected by qualified privilege, the defendant must have made the statement in good faith, without malice, and in a situation where the communication was necessary or appropriate. For example, a former employer providing a reference for a former employee may be protected by qualified privilege, as long as the reference was made in good faith and without malicious intent.

Opinion vs. Fact

As mentioned earlier, statements of opinion are generally not considered defamatory because they cannot be proven true or false. This defense hinges on whether the statement in question is a factual assertion or merely an opinion.

Courts will often look at the context of the statement to determine whether it is an opinion or a fact. For example, a restaurant critic who writes that “the food was terrible” is expressing an opinion, which cannot be the basis for a defamation claim. However, a statement like “the restaurant has a history of health code violations” could be considered defamatory if it is false, as it is a factual assertion.

Consent

Another defense to defamation is consent. If the plaintiff consented to the publication of the defamatory statement, they cannot later sue for defamation. Consent can be explicit or implied, and the scope of the consent is important. For example, if someone agrees to an interview and consents to the publication of certain statements, they cannot later sue for defamation based on those statements.

5. The Role of the U.S. Constitution in Defamation Law

Defamation law is significantly influenced by the U.S. Constitution, particularly the First Amendment, which protects freedom of speech. The interplay between defamation law and constitutional rights has led to the development of specific rules and standards that apply in defamation cases, especially when the plaintiff is a public figure or the statement involves matters of public concern.

Public Figures and Actual Malice

One of the most important constitutional principles in defamation law is the “actual malice” standard established by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964). In this case, the Court held that public officials must prove actual malice to succeed in a defamation claim. Actual malice means that the defendant made the statement with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard for whether it was true or false.

This standard was later extended to public figures in Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts (1967). Public figures include individuals who have achieved fame or notoriety, such as celebrities, politicians, and business leaders. The rationale behind the actual malice standard is to protect open and robust debate on matters of public interest, even if it means that public figures are subject to false statements.

Private Individuals and Negligence

For private individuals, the standard of proof is lower than for public figures. In Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974), the U.S. Supreme Court held that private individuals do not need to prove actual malice to recover damages for defamation. Instead, they must show that the defendant was negligent in making the false statement.

Negligence means that the defendant failed to exercise reasonable care in determining the truth or falsity of the statement. This lower standard recognizes that private individuals are more vulnerable to defamation and do not have the same access to the media to defend themselves as public figures do.

Constitutional Constraints and Gray Areas

While the actual malice standard provides strong protection for freedom of speech, it has also created gray areas in defamation law. For example, determining whether someone is a public figure or a private individual can be complex, and courts have struggled with this issue in various cases. Additionally, the rise of social media has blurred the lines between public and private individuals, as ordinary people can achieve fame or notoriety quickly.

The U.S. Supreme Court has also grappled with the issue of “involuntary public figures” — individuals who become public figures through no fault of their own, such as victims of crime or accidents. The Court has generally been reluctant to extend the actual malice standard to these individuals, recognizing that they should not be subjected to the same level of scrutiny as those who voluntarily seek public attention.

6. The Broader Implications of Defamation

Defamation has far-reaching implications for individuals, the media, and society as a whole. It can affect personal relationships, careers, and reputations, and it plays a significant role in shaping public discourse.

Impact on Individuals and Reputation

For individuals, defamation can have devastating effects on their personal and professional lives. A false statement can damage relationships, lead to job loss, and cause emotional distress. In some cases, the damage to reputation can be so severe that it is difficult to recover, even if the defamation claim is successful.

The law of defamation provides a remedy for those who have been wronged, but the process of pursuing a defamation claim can be long and expensive. Additionally, proving defamation can be challenging, especially for public figures who must meet the high standard of actual malice.

The Media and Defamation

The media plays a crucial role in informing the public and holding those in power accountable. However, the media is also a frequent target of defamation claims, as journalists and news organizations often publish statements that can harm the reputations of individuals and businesses.

Defamation law seeks to strike a balance between protecting reputations and ensuring that the media can report on matters of public interest without fear of legal retribution. The actual malice standard, for example, provides a higher level of protection for the media when reporting on public figures, recognizing the importance of a free press in a democratic society.

However, the media is not immune to defamation claims, and there have been cases where news organizations have been held liable for publishing false statements. In these cases, courts have emphasized the need for journalists to exercise due diligence in verifying the accuracy of their reporting.

The Role of Social Media in Defamation Cases

The rise of social media has transformed the landscape of defamation law. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have made it easier for defamatory statements to spread rapidly and reach a wide audience. This has led to an increase in defamation cases involving social media posts, with courts having to address new legal questions about the responsibility of social media users and platforms.

One of the challenges posed by social media is the question of who is liable for defamatory content. In the United States, the Communications Decency Act (CDA) Section 230 provides immunity to online platforms for content posted by users, meaning that social media companies are generally not held liable for defamatory statements made by their users. However, individual users can still be sued for defamation if they post false and damaging statements.

Another challenge is the issue of anonymity on social media. Many users post defamatory statements under pseudonyms, making it difficult for plaintiffs to identify and sue the responsible party. Courts have developed procedures for unmasking anonymous defendants, but the process can be complex and time-consuming.

7. Conclusion: Balancing Free Speech and Reputation

Defamation law is a complex and evolving area of law that seeks to balance two important values: the right to free speech and the right to protect one’s reputation. The law provides a remedy for individuals whose reputations have been unjustly harmed by false statements, while also recognizing the importance of free speech in a democratic society.

As society continues to evolve, particularly with the rise of digital communication and social media, defamation law will continue to face new challenges. Courts and lawmakers must navigate these challenges to ensure that the law remains relevant and effective in protecting individuals and promoting open discourse.

For individuals, understanding defamation law is crucial for protecting their rights and reputations in an increasingly interconnected world. Whether dealing with defamatory statements in the media, online, or in personal interactions, the principles of defamation law provide a framework for seeking justice and accountability.

In the end, defamation law serves as a reminder of the power of words and the responsibility that comes with that power. Whether spoken, written, or shared online, words have the potential to uplift or destroy, to inform or mislead. The law of defamation ensures that when words are used to cause harm, there is a mechanism for seeking redress, while also safeguarding the freedom to speak truth to power.

Defamation is a false statement made about someone to a third party, which damages the person’s reputation.

Defamation is the general term, while slander refers to spoken defamation, and libel refers to written or published defamation.

No, opinions are not considered defamation. Defamation requires a false statement of fact that can be proven true or false.

Yes, false statements made on social media that harm your reputation can be grounds for a defamation lawsuit.

The U.S. Constitution requires public figures to prove “actual malice” in defamation cases, meaning the defendant knew the statement was false or acted with reckless disregard for the truth.