The recent petition to restrain the release of the film Diary of West Bengal has sparked a vital legal debate regarding the delicate balance between freedom of expression and maintaining public order. The case, which was heard in the Calcutta High Court, highlights the ongoing tension between creative freedom and the potential for communal disharmony, raising important questions about censorship, public interest, and the role of the judiciary in protecting both individual rights and societal harmony.

In this blog, we will analyze the legal aspects of this petition, the court’s response, and the broader judicial precedents that apply. The core legal issues raised—ranging from free speech under the Indian Constitution to the proper use of public interest litigation (PIL) and the role of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC)—are critical for understanding the ongoing discourse on censorship in India.

The Petition: Concerns and Legal Grounds

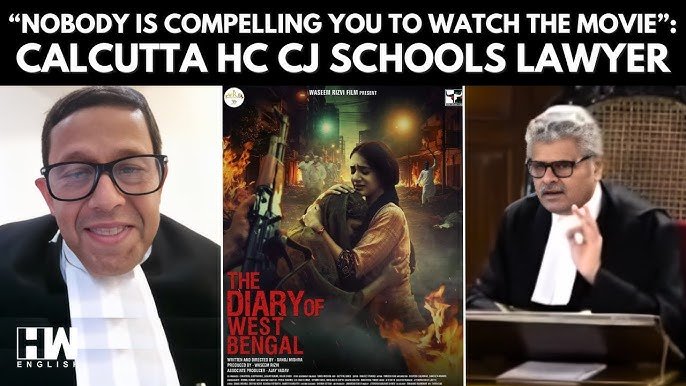

At the heart of the petition is the argument that Diary of West Bengal portrays the Chief Minister of West Bengal in a negative light, with the potential to incite communal tensions between different communities. The petitioner sought an injunction to prevent the release of the film, citing concerns about public order, communal harmony, and the Chief Minister’s personal reputation.

The petitioner referred to Section 5B of the Cinematograph Act, 1952, which provides that a film may be refused certification if it is likely to incite communal violence, affect public morality, or undermine public order. The central claim was that the film, by allegedly defaming the Chief Minister and promoting discord between communities, violated this section of the Act and should not be allowed to be released in public theaters.

The petitioner’s argument also touched on the right to privacy and the potential damage to the Chief Minister’s reputation, invoking the idea that films portraying public figures in a defamatory manner could infringe upon their dignity.

The Chief Justice’s Response: Upholding Democratic Freedoms

The Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court took a strong stand in favor of democratic principles and the right to free expression, reminding the court that in a democracy, individuals have the autonomy to choose whether they wish to engage with particular content. His remarks highlighted a broader judicial philosophy that has been reiterated in several key rulings: unless a piece of content directly threatens public order or violates the law, it cannot be restrained merely because it offends or criticizes certain individuals.

The Chief Justice pointed to landmark judgments where the courts have ruled against banning books, films, or other forms of media based on subjective offense. Instead, he suggested that individuals who are personally aggrieved—such as those depicted in the film—should come forward to file a defamation suit or other legal action, rather than using a PIL to suppress creative expression.

As he remarked during the hearing, “If it is up to you, you want to watch the movie, you watch the movie. You don’t want to read the book, you don’t. Nobody is compelling you.” This judicial viewpoint aligns closely with the principles laid down in Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression, subject to reasonable restrictions outlined in Article 19(2).

Public Interest Litigation: A Powerful Tool, But With Limits

One of the most important elements of this case is the use of a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) to challenge the film’s release. PILs are a unique feature of the Indian legal system, designed to allow any member of the public to bring a case to the court in matters that concern the welfare of the public at large. However, PILs are also subject to limitations, and the courts have cautioned against their misuse.

In the present case, the Chief Justice expressed concerns about the overuse of PILs to challenge creative works. He pointed out that such petitions, if allowed to proceed unchecked, could overwhelm the judiciary, leading to a flood of cases that stifle creative freedom without addressing genuine public interest. His comments reflect the judicial sentiment expressed in cases such as Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India (2016), where the Supreme Court warned against the misuse of PILs to advance personal or political agendas.

The Chief Justice’s remarks about the use of PILs align with the long-standing judicial position that PILs should not be used as a tool for censorship by proxy. The courts have consistently upheld the principle that creative works should be allowed to flourish unless there is a clear and present danger to public order. This was exemplified in the S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989) case, where the Supreme Court ruled that a film’s release cannot be restrained simply because it may offend certain individuals or groups unless it directly incites violence or threatens national security.

Film Certification and the Role of the CBFC: Cinematograph Act, 1952

The petition to stop the release of Diary of West Bengal also touches upon the role of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), which operates under the Cinematograph Act, 1952. The CBFC is responsible for reviewing and certifying films before they are released to the public, ensuring that they comply with guidelines related to decency, morality, and public order.

In this case, the film had already received certification from the CBFC, and the petitioner’s argument centered around a trailer of the film that was available on YouTube, which had not been certified. The Chief Justice rightly pointed out that the proper course of action would be to approach the CBFC with any concerns about the content of the film, rather than seeking a judicial injunction to block its release.

The courts have consistently upheld the CBFC’s authority in matters of film certification, as demonstrated in the Bobby Art International v. Om Pal Singh Hoon (1996) case. In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that once a film has been certified by the CBFC, its release cannot be challenged because it offends personal or community sentiments.

The Right to Privacy and Public Figures: Legal Protections and Limitations

Another key argument raised by the petitioner is the alleged violation of the Chief Minister’s right to privacy, given that the film depicts her in a negative light. The right to privacy, recognized as a fundamental right under Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017), includes the right to protect one’s dignity and reputation.

However, this right is not absolute, particularly when it comes to public figures. In R. Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu (1994), the Supreme Court held that public officials are subject to greater scrutiny and criticism, as their actions are of public interest. As long as the portrayal is based on facts and does not amount to defamation, the right to free speech prevails over the right to privacy in the case of public figures.

In the context of Diary of West Bengal, the portrayal of the Chief Minister may indeed be unflattering, but as long as it is factually based and does not constitute defamation, it would likely fall within the scope of legitimate criticism. Public figures, especially politicians, are often the subject of critical media and creative works, and the courts have historically protected such works under the banner of free expression.

Key Judicial Precedents on Film Censorship

The legal landscape surrounding film censorship in India is shaped by several landmark cases, many of which were referenced in the hearing on Diary of West Bengal. One of the most significant is S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989), where the Supreme Court held that a film’s release cannot be restrained unless it poses a clear and present danger to public safety or national security. The court emphasized that the subjective offense taken by individuals or groups is not sufficient grounds to block a film’s release.

Another key case is Prakash Jha Productions v. Union of India (2011), where the Supreme Court upheld the release of the film Aarakshan despite concerns that it would inflame caste tensions. The court ruled that once a film has been certified by the CBFC, its release cannot be blocked unless there is clear evidence of imminent harm to public order.

These precedents underscore the judiciary’s commitment to protecting free expression while balancing concerns about public order and morality. In the case of Diary of West Bengal, the Calcutta High Court’s Chief Justice appears to be following this well-established legal framework, urging the petitioner to approach the CBFC and avoid using the courts as a means to stifle creative expression.

Conclusion: The Way Forward for Diary of West Bengal

The petition to restrain the release of Diary of West Bengal raises critical questions about the limits of free speech, the proper use of public interest litigation, and the role of the CBFC in regulating creative content. While the concerns raised by the petitioner are not without merit, the legal principles that govern such cases are clear: free expression is a cornerstone of Indian democracy, and any attempt to restrict it must be based on solid legal grounds.

The Calcutta High Court’s Chief Justice emphasized the importance of allowing individuals to choose whether or not to engage with creative works, and reminded the petitioner that the proper course of action is to approach the CBFC with concerns about the film’s content. As the case progresses, it will likely serve as a reminder of the judiciary’s commitment to protecting creative freedom while balancing the need to maintain public order.

In conclusion, the Diary of West Bengal case reinforces the importance of adhering to established legal processes when dealing with creative content. While public figures may be the subject of criticism or unflattering portrayals, the courts have consistently upheld the right to free speech, provided it does not incite violence or threaten public safety. For filmmakers, artists, and legal practitioners, this case serves as an important reminder of the limits of censorship and the need to respect both creative freedom and the rule of law.

Yes, films in India can be censored under the Cinematograph Act, 1952, through the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). The CBFC has the authority to certify, modify, or ban films if they violate public order, decency, or morality. However, courts typically uphold creative freedom unless there is a clear threat to public order or safety.

he petitioner argued that Diary of West Bengal depicted the Chief Minister of West Bengal in a negative light and had the potential to incite communal tensions. They sought to block the film’s release, citing concerns about public order and the defamation of a public figure.

The Calcutta High Court, emphasizing freedom of expression, suggested that the right course of action was to approach the CBFC for content review rather than using public interest litigation to block the film. The court highlighted that in a democracy, individuals are free to choose whether to watch or engage with creative content.